Bayesian Hide-And-Seek, Anyone?

1. General Game Summary: Hide and Seek

For those who haven’t seen the “Hide and Seek” format of Jet Lag: The Game, the premise is simple: One person hides in a massive geographic “endzone” (like all of Switzerland), and the others have to find them. The hider stays put, but as time passes, they must answer questions or provide clues. The longer they stay hidden, the more points they earn.

The Objectives of the game are relatively simple:

- The Seekers: Their goal is to collapse the search area and “lock down” the hider’s location. While the show awards the win to the longest run, for any individual round, the seekers are attempting to find the hider in minimal time.

- The Hider(s): Their job is to stall and delay the seekers for as long as possible, while truthfully answering the seeker’s various questions. They also get to draw various cards in the game as rewards for answering the questions, which include benefits like additional time bonuses and curses (tasks the seekers have to complete before asking further questions).

Reference: [Jet Lag: The Game - Hide And Seek Switzerland, Season 9 Episode 1]

2. Delving into The Game

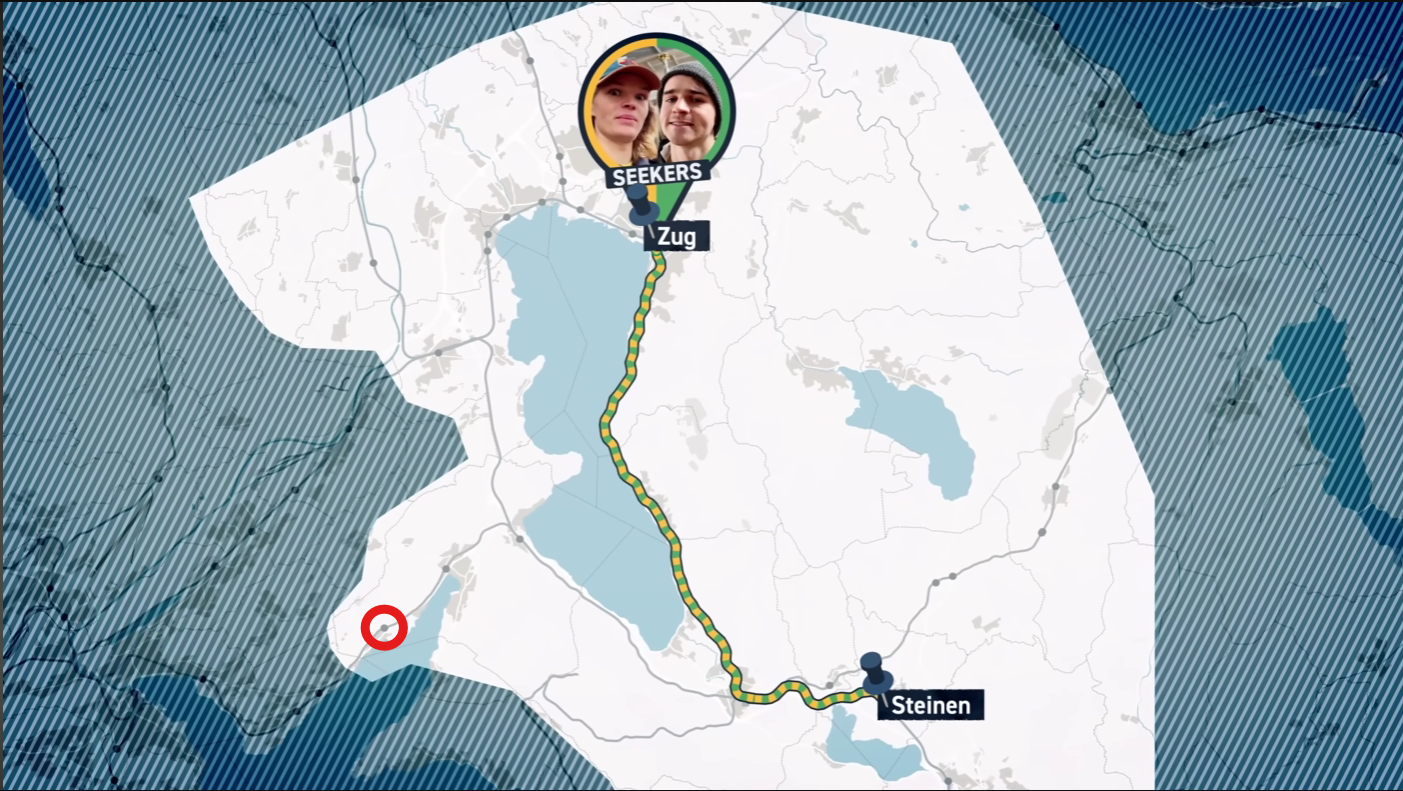

In practice, the game moves from broad geographic partitions to granular “street-level” hunting. Across the various seasons of Jet Lag, some more common strategies emerge.

Seeker Strategies:

- Direct Elimination: A binary search approach. “Are you North of this line?” This slices the map in half, regardless of the hider’s cleverness.

- Aggressive vs. Passive: Aggressive seekers move early on low information, betting on intuition. Passive seekers wait for high-confidence clues to avoid wasting travel time.

Reference: [Jet Lag: The Game - Hide And Seek Switzerland, Season 9 Episode 2]

Hider Strategies:

- Truthful Misdirection: Providing a clue that is factually 100% true but contextually misleading. One example is if asked “Take a photo of the nearest body of water”, the hider might zoom in so closely on a water body that it’s impossible to tell if it’s a small pond or a lake or even an ocean.

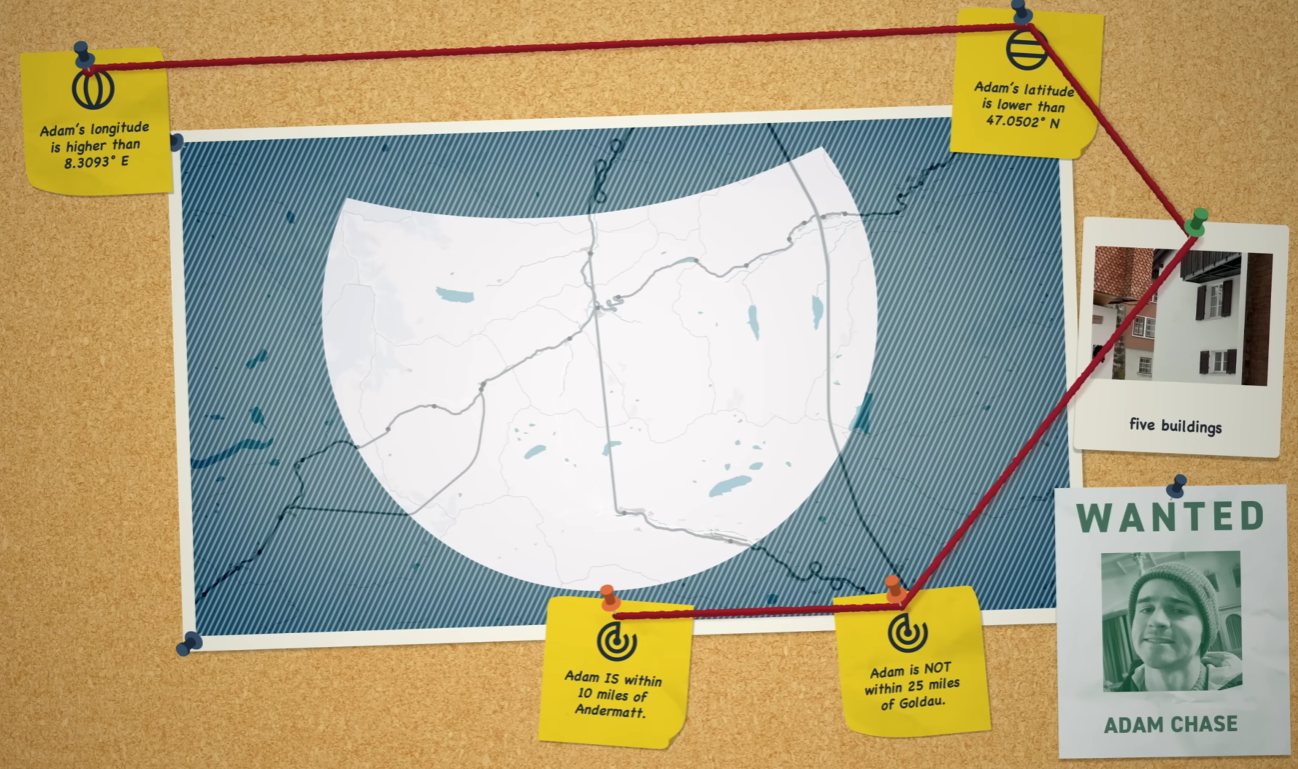

- Information Minimization: Giving essentially useless answers where possible, while still satisfying the minimum criteria of the respective question. If asked a broader question such as “Take a photo of 5 buildings”, a hider might try to find a cluster of buildings that are relatively commonplace, making it challenging to determine whether it is within an urban dense area or city suburbs or even a small town.

Reference: [Jet Lag: The Game - Hide And Seek Switzerland, Season 9 Episode 1]

3.1. Bayesian Theory, Anyone?

One interesting insight would perhaps be how some Bayesian Theory concepts could apply in this game context.

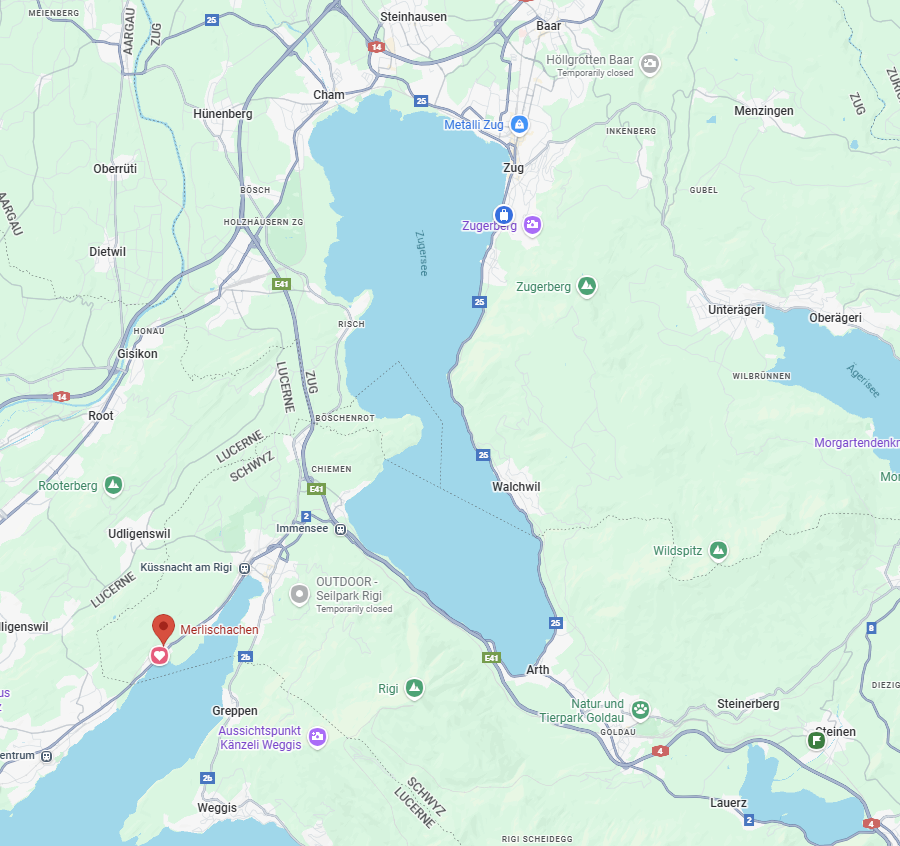

Firstly, technically the search space is finite and is discrete as well (except the endgame within the endzone, let’s focus on the early to mid-game); a finite number of possible hiding locations all possessing different features.

In the early game when asking questions like “Are you north or south of me?”, it is essentially bundling the hiding locations into sectors, and from there narrowing down the options based on the provided information. And of course, based on the answers being able to segment out various sections of the possible hiding locations.

Plus, when the hiders ask the seekers various questions in this endless process, the hiders are getting more information and being able to further hone in on the seeker’s location with higher confidence.

So to some extent, it can be said that:

- The game map is a finite, discrete world model of hiding locations

- These hiding locations are possible goal states

- The process of searching for the seeker is essentially partitioning the search area narrower and narrower until only one hiding location remains

- In the early to mid game where the search space is relatively big, the hiding locations are grouped into partitions

- And based on the continuous question-answer-question-answer process, these partitions are splintered into smaller partitions composed of goal states

- And these partitions can be subsets, intersections, unions or any mix of these properties

And for the seekers:

- They are using the questions to gather information on where the hider could be

- At the start since there is no information, the notion of the hider being anywhere can be represented as a uniform probability distribution over all locations

- Each question-and-answer then assists in updating their existing beliefs or probabilities over the various goal locations possible

- And this happens continuously till only one goal location remains

3.2. A Possible Bayesian Model

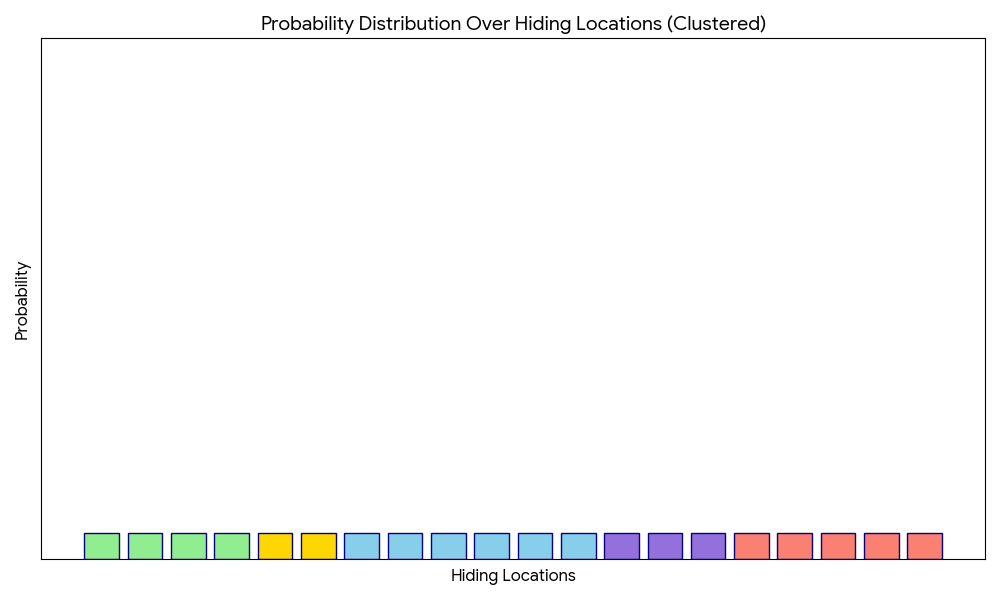

Without too much technicalities (for now), let’s assume the various sectors (of hiding locations) are clustered based on some condition; it can be anything, like whether north or south, east or west, or district in the game zone. Idea is a general cluster that has 2, or usually more, sub-groups. Let’s denote these various clusters through various colours.

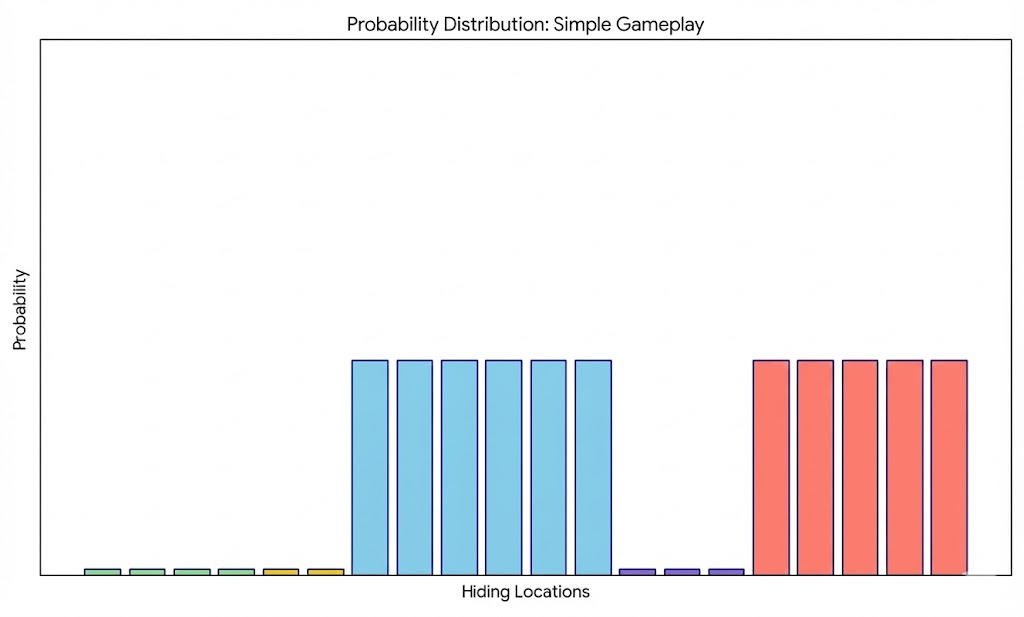

3.2.1. A Typical Standard Gameplay

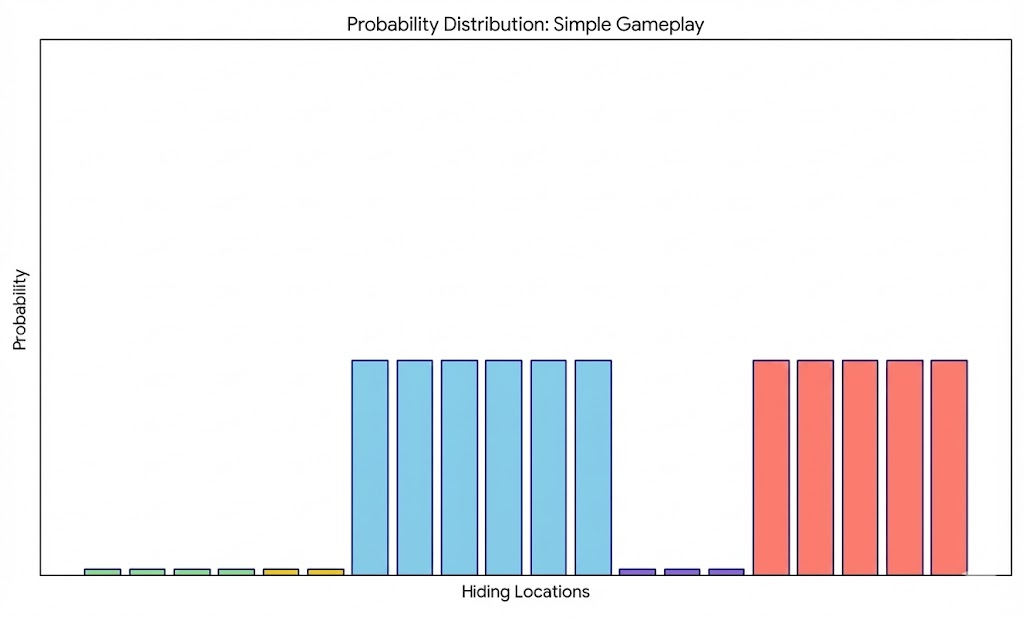

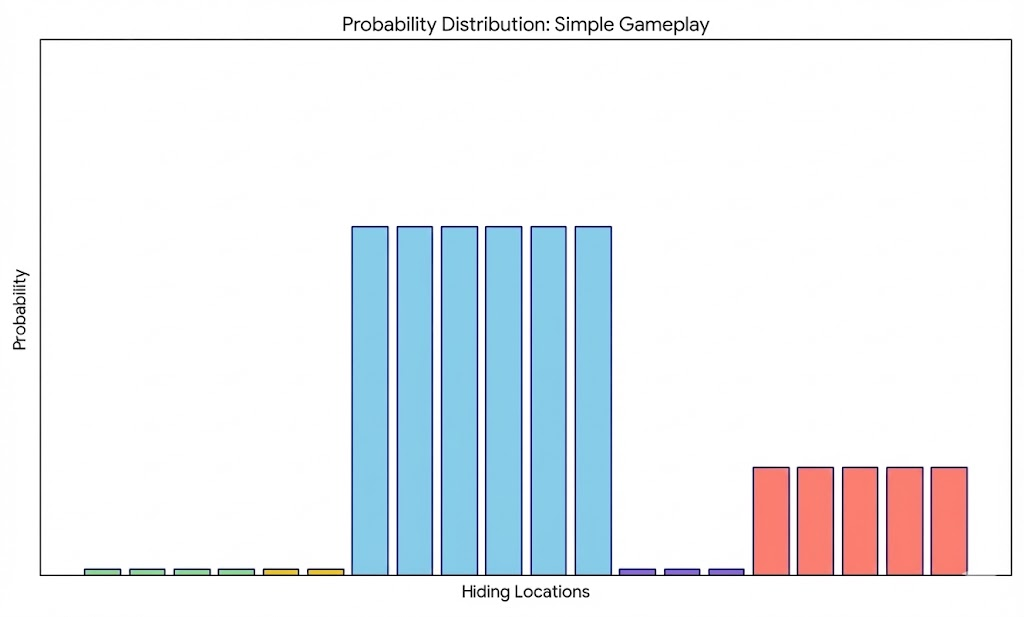

A possible, typical gameplay may be depicted as follows. The seekers ask a variety of questions, and with each question is able to hone in on various options which narrows the possibilities.

3.2.2. Hider Tactics

Misdirection

Recap: Providing a clue that is factually true but contextually misleading. One example is if asked “Take a photo of the nearest body of water”, the hider might zoom in so closely on a water body that it’s impossible to tell if it’s a small pond or a lake or even an ocean.

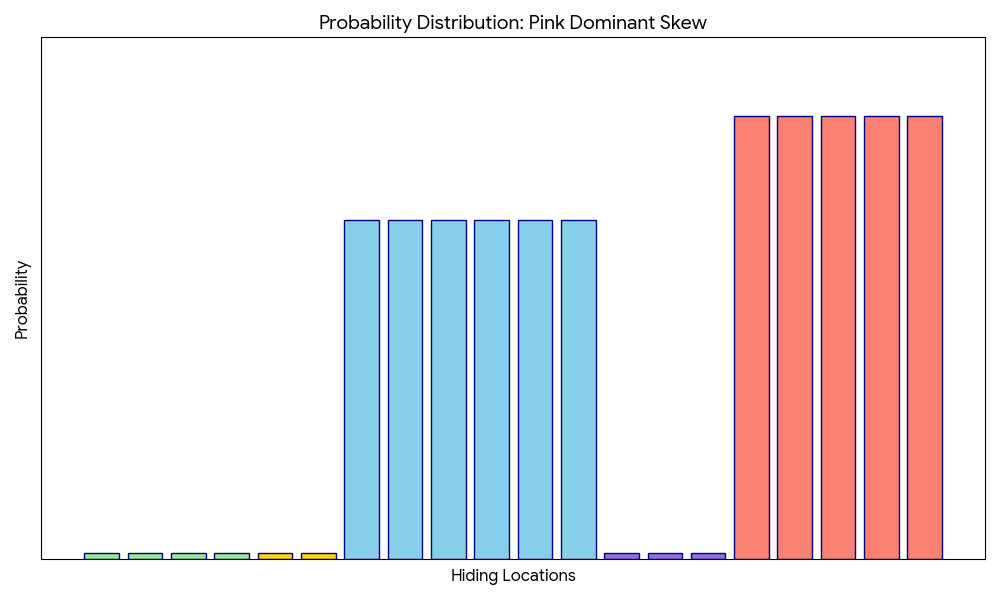

In probability terms, this could be represented as a deliberate attempt to shift the seeker’s high-confidence to incorrect location(s).

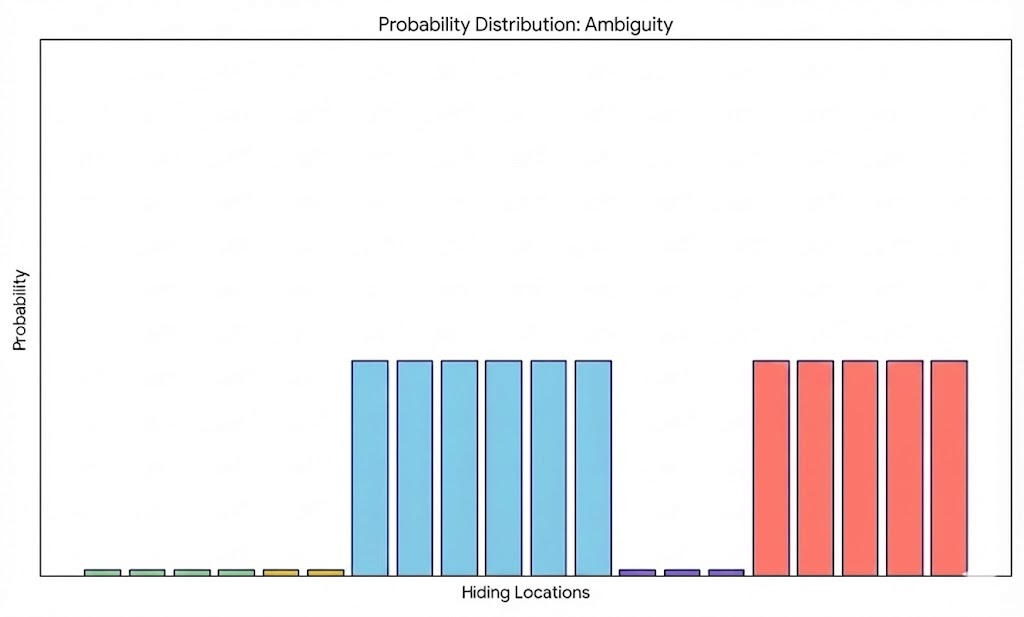

Ambiguity

Recap: Giving essentially useless answers where possible, while still satisfying the minimum criteria of the respective question. If asked a broader question such as “Take a photo of 5 buildings”, a hider might try to find a cluster of buildings that are relatively commonplace, making it challenging to determine whether it is within an urban dense area or city suburbs or even a small town.

In probability terms, the hider provides as redundant data as possible, leading to the seeker’s posterior remaining minimally changed or even totally unchanged. In turn, the seeker remains paralyzed, and the hider gains time.

3.2.3. Seeker Tactics

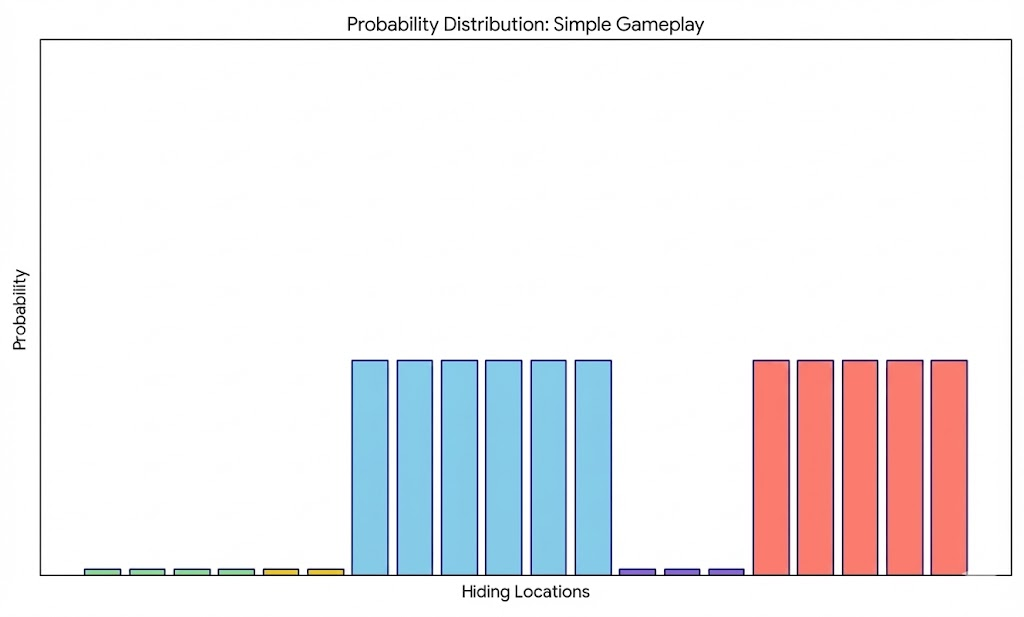

Slow-And-Steady

Such an approach ensures a search process with high-confidence, which typically entails evidence that can completely eliminate certain possibilities. While it could be argued as overly conservative, but it offers seekers an efficient and clean approach with minimal backtracking on earlier clues.

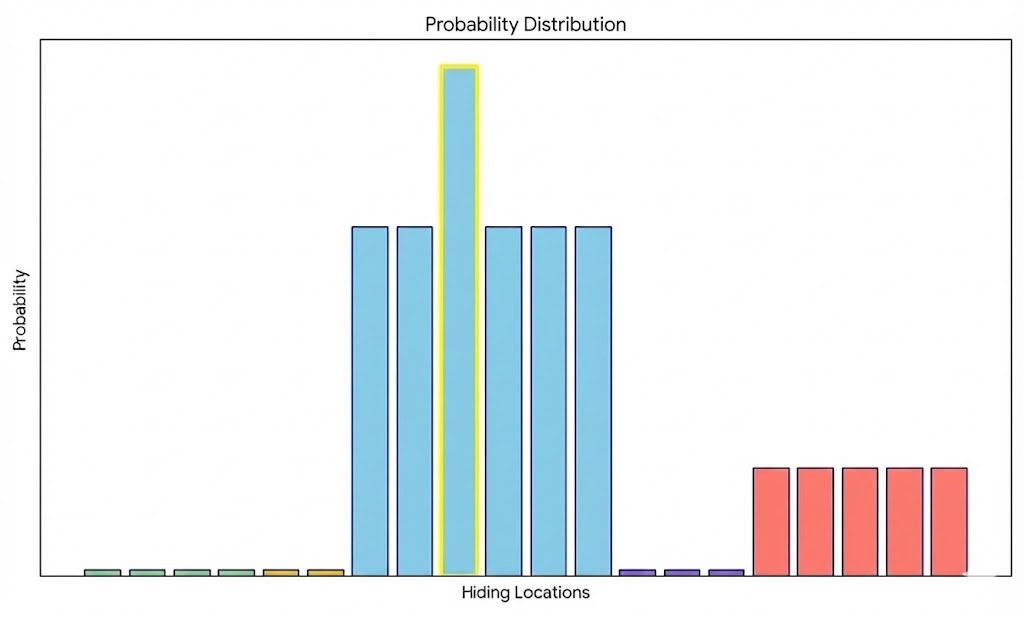

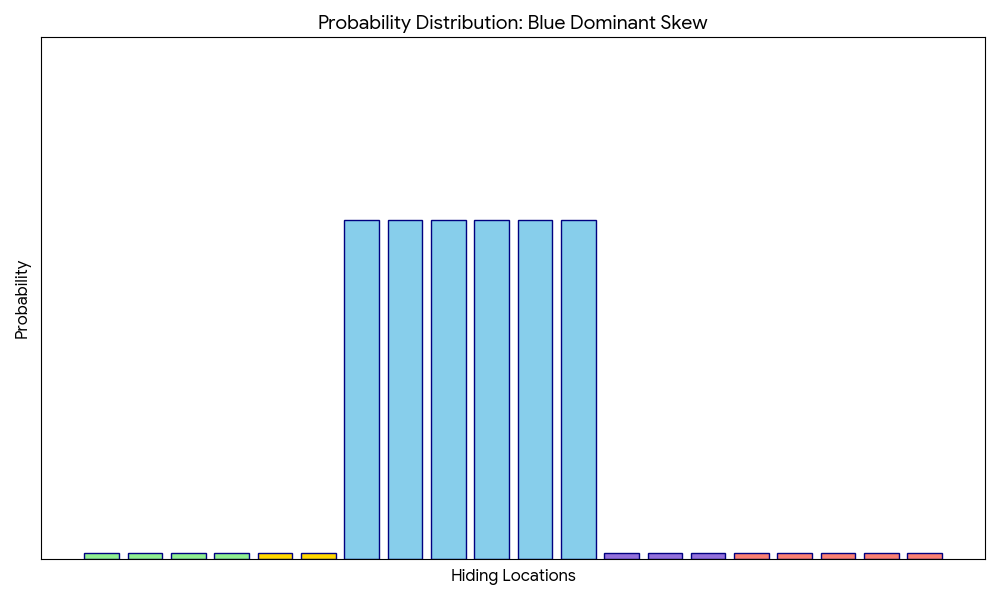

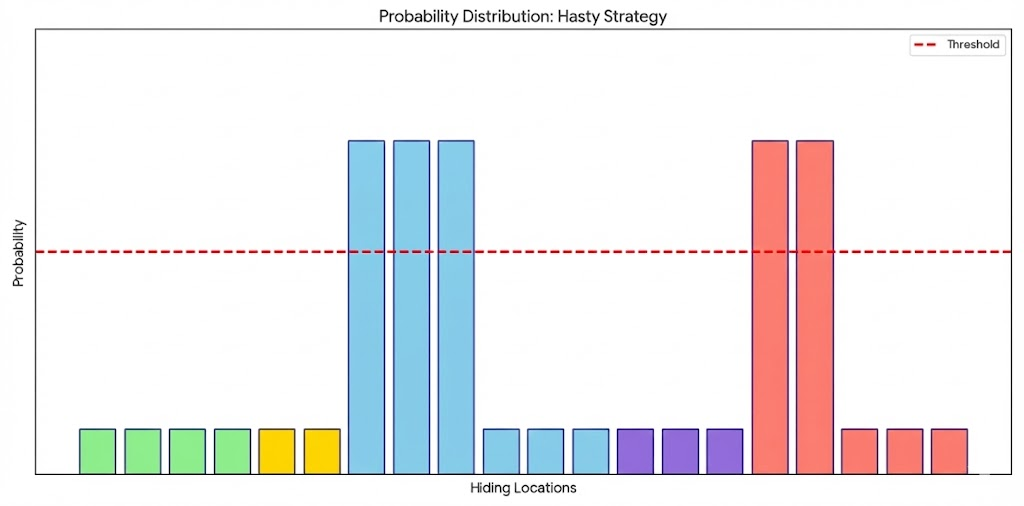

Fast-And-Furious

Serving as the relative opposite of the above approach, where seekers who adopt this strategy typically desire to aim to find the hider as soon as possible. This requires greater risk and managing of uncertainity, namely depicted by seekers who “commit” or zoom in on a particular location (or group of locations) once it surpasses a self-defined “confidence” threshold value, although it poses as non-guaranteed certainity. While it does pay off sometimes in the form of a rapid search process, but it also has yielded instances where seekers made a massive error.

Do note that while the image shows numerous candidate locations that lie above the threshold with equal uniform probability, in reality there could be tiny fluctuations that dictate a preference order among options. Possible selection strategies can then be adopted, with an arguably common approach to select one-by-one in descending order of probability.

4. The Technical Part, Anyone? (Optional, Feel Free to Skip)

4.1.1 Game Variables: Hiding States

We define the environment as a set of discrete, finite potential hiding locations $G$.

Hiding States ($G$): $G = {g_1, g_2, \dots, g_n}$, where each $g$ represents a specific geographic partition or coordinate.

We then define each hiding state $g \in G$ as a finite, countable binary feature vector:

\[g = (x_1, x_2, \dots, x_k, \dots, x_K)\]Where:

- $x_k \in {0, 1}$: Each element is a boolean value representing the presence (1) or absence (0) of a specific attribute.

- $K$: The total number of unique features

Clarification: It can be argued that a more intuitive approach would be to associate a goal state with direct geographic data, eg a proper name, GPS coordinates, or continuous values like population density. However, it could also be noted that transforming these into a 0/1 boolean representation is a strategic simplification; by binarizing the environment, it is then possible to convert complex spatial questions into simple logical gates, which greatly assists in the partitioning phase by allowing the Seeker to aggregate locations into discrete subsets subsequently.

4.1.2 Game Variables: Continuous Question-And-Answer

Evidence Stream ($E$): The interaction consists of a series of evidence (questions and answers pairs from the conversation between hiders and seekers) $E_1, E_2, \dots, E_N$.

Cumulative Knowledge ($K$): The total information possessed by the Seekers at and up to turn $N$ is represented by the set of all observed evidence, as part of the question-answer pairs, collected. This can be represented as:

\[K_N = \bigcup_{i=1}^{N} E_i\]Where:

- $E_i$: Represents an individual piece of evidence (the $i$-th question and answer pair).

- $\bigcup_{i=1}^{N}$: The aggregation of all evidence from the first turn up to the current turn $N$.

- $K_N$: The resulting Knowledge base that the Seekers use to then perform their Bayesian update.

4.2. Partition Logic

Each question aims to create a partition $P$ over the state space $G$ to divide $G$ into subsets and eliminate unlikely candidates.

A partition is established when a Seeker asks a question that targets a specific feature $x_k$. This effectively “sorts” the universal set $G$ based on the boolean value of that feature index. For any question targeting feature $k$, the partition can then be defined by partitioning the set of all locations into where the feature exists and where the feature is absent.

In particular, For any question targeting feature $k$, the partition $P$ is defined as:

\[P = \{S_{\text{TRUE}}, S_{\text{FALSE}}\}\]Where:

- The set of all locations where the feature exists: \(S_{\text{TRUE}} = \{g \in G \mid x_k = 1\}\)

- The set of all locations where the feature is absent: \(S_{\text{FALSE}} = \{g \in G \mid x_k = 0\}\)

Example: The Binary Partition

This is a relatively common, and arguably, simple-yet-effective move. As an example, let’s assume a question divides the possible candidates into 2 clear subsets - “Are you North of my location?”. Note other similar questions could also come in the form as “Are you closer (than me) to a major airport?”.

The question naturally defines a partition over 2 subsets $S_1$ and $S_2$, as represented by \(P = \{S_1, S_2\}\).

Hider’s Evidence: By answering, the Hider indirectly “selects” one subset, allowing the Seeker to set the probability of all $g$ in the other subset to zero.

Similar to the continuous question-and-answer mechanism in the game till the seekers discover the hider’s location, this partitioning happens repeatedly throughout which fractures the candidate subsets smaller and smaller.

4.3. Bayesian Update

In this framework, the Seeker’s knowledge at turn $N$ serves as the foundation (the Prior) for the incoming evidence at turn $N+1$. The update to the Posterior Distribution is represented proportionally:

\[P(g \mid K_{N+1}) \propto P(E_{N+1} \mid g) \cdot P(g \mid K_N)\]Where:

- $P(g \mid K_{N+1})$ (The New Posterior): The probability that the Hider is at location $g$ after integrating the latest clue $E_{N+1}$ into the existing knowledge base.

- $P(E_{N+1} \mid g)$ (The Likelihood): The probability of receiving the specific answer $E_{N+1}$ if the Hider were truly located at $g$.

- $P(g \mid K_N)$ (The Current Prior): The Seeker’s existing belief distribution, which was established based on the knowledge base up to turn $N$.

- Uniform Prior Assumption: We initialize the knowledge base of potential goal locations with a Uniform Prior, where every location is considered equally likely.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: